|

|

| In

1337, the military reputation of England was not high, but they soon

became the most feared troops in Europe.

The battle tactic of dismounting men-at-arms and combining

them with flanking archery, developed against the scots provided

almost unbeatable. Numbers

of archers grew during the war from one to one or less in proportion

to men-at-arms, to two to one or more.

In addition, English armies were very mobile.

Experience in Scotland and Ireland had developed the hobilar,

a light horseman useful in raids.

A rising proportion of archers served mounted, as their

status and income rose, squeezing out peasant participation.

English armies increasingly served for pay through

‘indenture’, whereby captains, ranging from great lords to

esquires, contracted to provide an agreed number of men.

This was a flexible system well-suited to overseas

expeditions, and called ‘professional’ armies. |

|

In

contrasts, French armies depended heavily upon the military

obligations of the chivalrous classes, providing men-at-arms, and a

levied infantry or town militias, often of poor quality.

Missile-men were commonly Genoese mercenary crossbowmen,

drawn from the royal fleets. Such

forces proved difficult to muster, being tied down in garrison duty,

and being tactically inflexible in the face of the English

‘system’.

Certainly

English tactics were crucial in providing victories, often against

the odds, but this does not mean that the English strategy of

chevaucje was a battle-seeking one. The chevauchies resulting in the battles of Crecy (1346) and

Poitiers (1356) were untypical, although both gave Edward important

political advantages. The

chevauchies of the 1370’s and 1380’s were less successful.

The French had learnt not to offer battle, and the English

gained no fortifications. |

| |

|

|

|

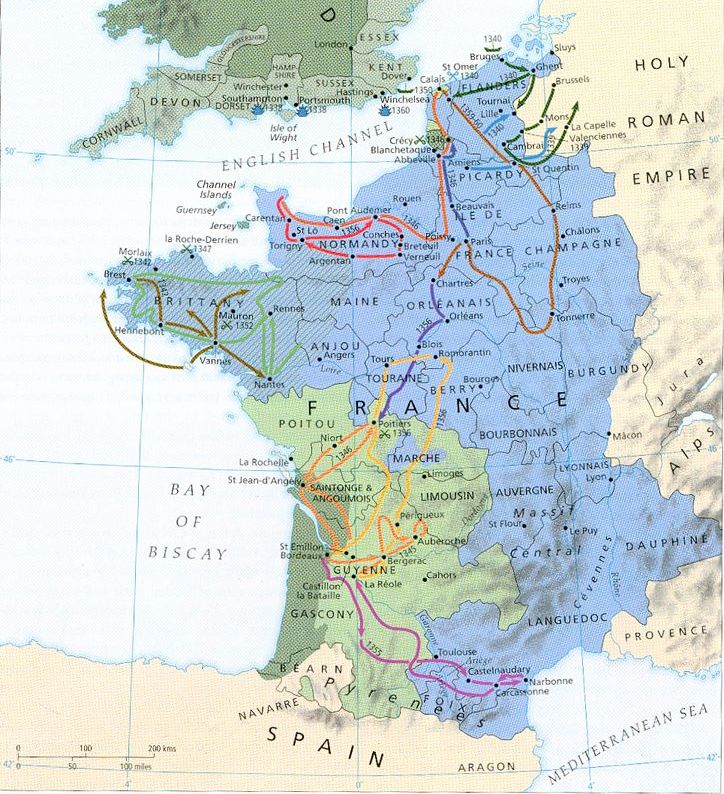

1340 saw the

first real conflict between France and England with the Battle of

Sluys. The outcome of

this was a decisive English naval victory, but the following land

campaign achieved no more than an unsuccessful siege of Tournai.

These costly expeditions bankrupted the English government

and forced them to change strategy.

England adopted, for the next two decades, a style of

guerrilla warfare. The English established oppressive ransom

districts to support their garrisons in Brittany, whose captains

made fortunes.

In April

1356, John II (king of France since 1350) arrested Charles, king of

Navarre, for treachery. This

brought Philip of Navarre, Charles’ brother, into Edward’s camp,

this was a useful ally as the brothers’ estate included parts of

Normandy. Edward

seizing his chance redirected his troops, under Henry of Lancasters

command, intended for Brittany to Normandy, were they joined forces

with other ally units and lifted the siege of Pont Audemer, from

there they swept south via Breteuil, Conches and Verneuil were King

John mustered troops to slowly to oppose them. They continued to march south via Argentian then Torigny.

Lancaster then launched another chevauchee out of Brittany to join

up with prince Edward, who was advancing north from Bergerac. Edward spent 7-11 August at Tours, probably waiting for

Lancaster, whose advance was barred by the swollen Loire River.

Unaware of this Edward got trapped just south of Poitiers by

King John, who had learnt of Edwards’s positions by prisoners he

had captured. Edward

took up a strong position and was able to nullify John’s numerical

superiority and then managed to capture the French King (19

September 1356) and hold him for ransom.

Edward was

provoked in 1359 to invade North France again, over royal ransom

wrangling. He intended to take Reims and be crowned king there.

When the city defied siege, Edward, ever the opportunist,

gave up his claim to the French throne in return for confirmation of

the widest extent of lands held by the English crown for 200 years

(Treaty of Bretigny, 1360) His

original aim of securing Gascony had been greatly exceeded as the

campaigns of the 1340’s created their own momentum of plunder and

glory, and the windfall of King John’s capture gave him a trump

card in negotiations. His

strategy had won huge gains, but it was not to prove fallible.

|

|